One of the places I went to on my recent South China trip was the Guanling Lagerstätte. This is Late Triassic in age, about 220 million years old or so – so considerably younger than the rocks we normally look at. As is often the case in China, the fossil site has been made into a museum. There is a purpose-built building housing a lot of fossil material and a short walking trail around some of the outcrops. Some of the larger fossils (mostly ichthyosaurs) have been left in situ and had protective shelters built around them.

The photo shows slabs with lots of crinoids (sea lilies) on display in the museum. The crinoids are thought to have been attached to floating logs (although it’s only fair to say that this isn’t universally accepted, and the crinoids may have grown on sunken logs on the sea floor instead).

More photographs on flickr, showing marine reptiles, crinoids and their logs, and more of the museum displays.

Lucy

Tuesday, 29 November 2011

Guanling Lagerstätte

Saturday, 5 November 2011

Garden at Huanguoshu waterfall

It’s been a busy few weeks. After I came back from the conference in the US, I went off to Guizhou Province, South China for two weeks of fieldwork. The first week was with an Argentinian graptolite worker who was visiting Nanjing, so we went around already known sites. Some of them I had seen before, but it’s always good to go back to places, especially as I found a couple of sponges! For part of the week I “attended” the conference of the Palaeontological Society of China. “Attended” because I only went to the opening ceremony, and the rest of the time either worked in my hotel room or went to various interesting tourist sites with the Argentinian. There was little point in attending the talks, as they were entirely in Chinese and my language skills are not yet good enough to understand much.

The photo was taken in a garden at one of the sites we visited, called Huangguoshu Waterfall. I thought it looked like a stereotypically Chinese scene. The waterfall itself was about a hundred metres long, and there was a cave behind it, so it was possible to walk all the way round. Pictures of the waterfall are on my flickr photostream (click on the photo to follow the link).

The second week of fieldwork I went back to a site I had collected from earlier this year. I went to the site looking for graptolites, but also found various interesting things including worms. This time the worms were a bit lax in coming forward – none were found until the last hour of fieldwork, and then three came along in quick succession! I’m currently writing up a paper for publication, so more details will be forthcoming once that comes out.

Joe is currently in Canada looking at Burgess Shale sponges. I expect he will do a blog post about his adventures sometime.

Lucy

Saturday, 15 October 2011

Downtown Minneapolis

Perks of the Job

I’ve often heard it said that conferences are an excuse to have an expensive jolly, and justify it to the management. Too right. But that doesn’t mean it’s not important.

Last week we were in Minneapolis, Minnesota, for the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America. This is probably the biggest meeting we’ve been to, with something like 10,000 participants across all of the earth and planetary sciences. I reckon there were only a few hundred palaeontologists there, but that’s still a sizeable gathering (does anyone know the collective noun for palaeontologists? I dread to think…). For four days we mingled, muttered, harangued and bought drinks for each other, and we might even have learned something – all at the expense of a research grant (we used to pay for it ourselves, but now we live in luxury we can afford perhaps one of these per year). So how can we possibly justify jetting off to the other side of the world, staying in a hotel (well, hostel in our case) and eating in restaurants every night (well, most of them)?

Conferences are all about communication and collaboration. At a good conference, I am always amazed by what is achieved. Attending a conference in principle entails sitting down and listening to people present their work in 15-minute slots, from 8 in the morning until 5 at night, and slotting in the poster sessions between and after. In reality, there’s a lot more to it. There are times when the talks are really not relevant, and you go and talk to someone instead, but for much of the time you’re being presented with work that you otherwise wouldn’t read in paper form. In the process, you end up seeing all sorts of things that are relevant to you obliquely, or ideas that you can apply. For example, I saw a talk about the preservation of shell beds that showed that the most important aspect controlling what’s in them is not how much has been destroyed before burial, but rather how much mixing has gone on between the fossils from slightly different times. I don’t normally get to work on shell beds, but it’s an interesting idea regardless; it also matches what we see in modern bugs, where population proportions change dramatically from year to year. It’s one of many things we’re going to have to take into account in future.

If you’re going to a conference, you really ought to present. Firstly, a big part of the justification for going is that you are making your research accessible, and provides a stiff challenge to your results and reasoning: it’s an alternative to writing papers in a sense, although obviously it can never replace a permanent, published record of your ideas. Both of us gave talks this time, and they both went down surprisingly well – it must have been the quaint accents that did it. Lucy was talking about a comparison of three sites with soft-bodied fossils from the Early Ordovician (two of them new), and the announcement of new Lagerstätten always attracts attention. Her “exciting discoveries” were even mentioned in another talk on the last day, which is always nice – you know the message is getting through at that point. Mine was about early sponges, and how virtually everything that we think we know about them is probably wrong. It seems to have raised a few eyebrows, and one person made the “quotation mark” gesture when talking to me about hexactinellids, so again, the message obviously got through in some cases. This dispersal of ideas is crucial because hardly anyone works on sponges. Hopefully now some of the people who are seeing them in the field will have an idea of what might be important; aside from anything else, I had a few offers of collaborative projects across the world, and that can’t be bad.

Conference presentations also have the advantage that you can present ideas and discussions that are more speculative than the normal – things that might struggle with peer review, say. There was a wonderful example of that in Minneapolis, by Mark McMenamin (famed for his off-the-wall interpretations). In this case, he was interpreting a death assemblage of ten huge ichthyosaurs as being the result of predation by a Triassic Kraken. An apparently non-random arrangement of vertebrae in the remains he interpreted as being a deliberate, symbolic representation of its sucker array – the only non-human self-portrait in the fossil record. Now, I’m not saying that he’s right, but as he pointed out, cephalopods do have a high level of intelligence and are quite capable of catching things like sharks (e.g. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cA8zQw6gDNI). There’s also no doubt that ten big ichthyosaurs in one place, somewhere on the seabed off the coast, takes some explaining, and none of the previously suggested answers appear to work. Personally, I think it’s plausible… but that’s not really the point. This is what conferences can do – they present new ideas, new scenarios and new debates, and force us to think about them, no matter how daft they might first appear. Putting all those people in one place, for an intense few days of arguments and revelations, can’t help but lead to advances in the science.

So it’s not just a jolly. But yes, it is fabulous fun, and it means we get to see places we wouldn’t otherwise go. Lucy’s now back in China, and about to go on fieldwork in Guizhou, but I’ve stayed on in North America and am now in Toronto to work on the Burgess Shale sponges. More about that in a bit.

Sunday, 2 October 2011

Experiment in natural dyeing

I happen to find myself in need of a small amount of yellow wool, sufficient to crochet the beak and feet of a penguin (there is a good reason for this). I have white, black, red and green yarn, but no yellow. I could go out and buy a ball of yellow wool, but then I would be left with most of a ball of a colour that I don’t normally use. I could use red or green instead, but the resulting penguin would look a bit odd.

I decided to experiment with dyeing some of the white wool, using turmeric. I looked the subject up on the internet, and found that turmeric will work as a dye, but isn't very colourfast. This would be a problem if I wanted to make a garment, but isn't in this case, as the item I intend to make won't need to be washed very often.

I’ve done a little bit of dyeing before, and what is needed is not only some wool to dye and some colour to dye it with, but also something acid to make the colour stick. Vinegar or citric acid are often used. I don’t have any citric acid, and the only vinegar I have is very dark-coloured rice vinegar. I didn’t want to risk turning the wool black, so I bought a lemon and used the juice of one half.

On the left, the wool is soaking in a mixture of water and lemon juice. Making the wool wet before starting the dyeing process helps the colour to be taken up evenly. On the right is the prepared dye: I made it by mixing one teaspoonful of turmeric with a little hot water to the consistency of a thin paste. I then drained the soaking water and poured the turmeric mixture onto the wool. I used a plastic spoon to spread the paste, and squidged the yarn around with my fingers, to ensure even coverage.

I put the yarn into a plastic bag and steamed it in the rice cooker for about 15 minutes, then turned the rice cooker off and left everything to cool. I rinsed the yarn in the sink to remove any excess turmeric. Some of the colour came out at this point, but not much.

The experiment was a success: I now have yellow wool.

Friday, 23 September 2011

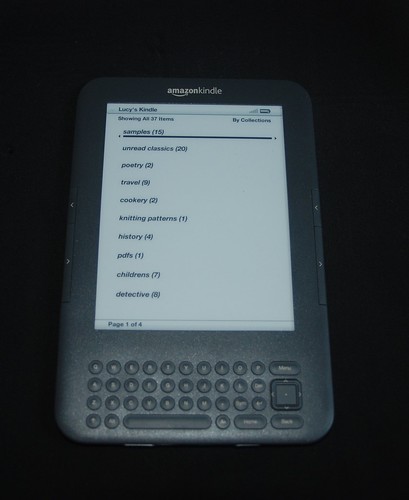

My kindle

When I was a child, the idea of a portable device that would hold thousands of books was science fiction. I recently bought one. Here it is.

There are several advantages to e-readers. The device is light in weight and small in size; smaller than an average paperback. The screen is easy to read, and the font size can be changed to allow for differing eyesight and lighting conditions. I can now carry enough books to be able to read through the entirety of a long flight – a thousand times over. I can read pdfs on the Kindle too, which means that I can now carry large chunks of my academic library with me. The device will even read some books out in a Stephen Hawking voice. The voice can be male (Stephen Hawking) or female (female version thereof) and the speed adjusted (very fast Stephen Hawking). Although the words are clear, the effect is slightly odd, as intonation is lacking. I don’t think I will be using this feature much, unless I buy A Brief History of Time, in which case it would be perfect.

Books are available almost instantly via the internet. This is certainly an advantage – no more waiting till I get to a bookshop/library before getting the next book in a series. This could also be a problem – I find I have to limit my visits to Amazon, although I usually manage to restrict myself to the free e-books.

There are some disadvantages to e-readers, too. I find they're not so good for things other than plain text. The screen only displays shades of grey, and some images just don't look right unless they're in colour. Also, flipping between an image and its caption is a nuisance, and even more so if you want to check something three pages back - for some things paper is definitely better! This isn’t a problem for most fiction, but for academic use it is often easier to print something out than to try to read it on-screen.

The most serious disadvantage of the Kindle is that it is an electronic device, which means that it has a finite (and not very long) life. Many of my paper books will be passed on to succeeding generations, but I am certain that my Kindle will not be. Even if it doesn’t suffer an accident that a paper book would have survived (for example, being dropped onto a hard surface), these things just die after a while. I can of course buy a new one and continue to read all the same books, as Amazon keeps a list of the ones I have downloaded. This will probably work out quite well, as I will have saved enough on not buying paper books (usually more expensive than the electronic version) to be able to afford another e-reader. However, it does mean that I have to keep spending money in order to keep reading items that I already own.

All in all, for my situation, in which books (at least ones that I can read) are expensive and the selection is limited, it's perfect. I will be using it mostly for fiction books, and not for academic texts. I certainly won’t be giving up buying paper books, but for light entertainment, where I am not too concerned about keeping a permanent copy, the Kindle will do nicely.

Lucy

Sunday, 18 September 2011

Caution - scientist at work!

This is what our office looks like. Joe is working, despite appearances - there is a good reason for having a cartoon character on his computer screen. I usually sit opposite him, with the printer between us. The room may look cluttered, but is in reality a very sophisticated filing system, in which the things we need most often – for example, tea mug – are most easily accessible. So, things like pens, printer and fruit bowl are on the desk between us, whereas dictionaries, envelopes and hammers are stored away in cupboards and drawers.

Our super-duper shiny new microscope is on a separate table, where there is plenty of room to draw. We normally keep it covered up unless we’re looking down it, to protect it from dust. The bit sticking out on the right of the microscope body is the camera lucida attachment. This is a wonderful device incorporating a mirror that allows the viewer to look at a fossil down the microscope and also see the paper to be drawn on. This allows one to make an accurate drawing just by going around the edges of the fossil – invaluable to those with little artistic ability.

The blue trays contain a small proportion of the fossils that we have to work with here. Most of the specimens are stored in the same type of tray on some large bookcases, but they don’t all fit there. This is another incentive to publish things quickly, before we run out of space altogether.

The windows are new; they were fitted in February, when the temperatures were below freezing. New ones were very necessary, as there was a pane of glass missing from the old ones, and they were very draughty in general. There was an insect screen concealing the missing pane, so it took us a while to work out where the icy blasts of air were coming from, and why the room never seemed to get warm.

There are more details of the things you can see, and other views of the office, on my flickr photostream (click on the photo to follow the link).

Lucy

Sunday, 11 September 2011

more little neighbours

It's been a while since we discussed some of our little multi-leggedy neighbours, so you deserve another installment.

At the end of our corridor, someone has placed some stacks of trays with rock samples outside their office. It's a nice quiet place with comfortable nooks and crannies... there are always open windows as well, so lots of small things for a hungry resident to entertain itself with. The resident in question is a uropygid, also known as a thelyphonid, a whip-scorpion, or a vinegaroon (a bit like a macaroon, but less coconutty).

Including the tail, it's nearly 10 cm long, but the body is a mere 4 cm or so. The tail is a long, hair-like structure that appears to be a sensory device – it certainly doesn’t have a sting, I’m glad to say. Lucy’s glad to hear that too, given that she almost stepped on it in the darkened corridor. (Or should that be, it almost stepped on her? Either way.) They can tell where they’re going by using those weird stringy legs at the front. They’ve evolved these in parallel with the antennae of insects, because uropygids are arachnids, and as such have no antennae. If you watch one of these moving, it will be tapping around in front of itself with those legs, searching for something yummy; its eyes are not that great, although it’s not actually blind, so it probably relies mostly on these to find its prey. This peculiar use of its front legs makes for another parallel with insects, as they only have six legs that they can walk with.

The things at the front are the equivalent of the palps of spiders – they’re not legs, but they evolved from them, once upon a time. They’re now used mostly to catch their unwary prey (mostly insects and millipedes, I’ve heard). The reason for the apparent overkill (although search for amblypygids if you think these ones are good) is that they don’t have a venomous bite, so the damage has to be done with the claws – or at least they have to be sure of holding things still for as long as it takes to nibble through them. Apparently they can’t do much damage to a human handler, although I imagine they’re a bit prickly. I was planning to try with the one in the corridor, just out of curiosity, but my finger thought better of it at the last second. Nothing should look quite so determined to go straight through whatever is in its path.

So why the vinegaroon moniker? Well, they do have a defence mechanism: they can squirt acid at something chasing them. It’s only a weak acid – vinegar plus something extra – but I imagine it might be offputting. Unless, that is, it’s chased by someone who’s quite familiar with fish and chip shops, in which case I guess it’s a self-condimenting treat. But it’s much more fun just to admire it when we get bored of writing papers or doing some statistical analysis. And of course we can leave the door of our office ajar so we can hear the occasional scream from the far end.

For those of a nervous disposition, there aren’t any of these in Europe. Except in pet shops.