From the sublime to... well, you get the idea. Some of you know I've been trying (and often failing) to write a series of fantasy books over the past few (well, fifteen) years. Thanks to the wonders of Kindle, I've finally gone and published the thing. You know how people always say how hard it is to get something into print? Well, it's true - unless that's just because mine's awful, of course...

Anyway, it's with a strange sense of trepidation that I can say that 'The Ghost of the Ocean', being the first part of 'The Whispering Rooms', is now available for the purpose of immediate boredom-relief* to anyone with a kindle (or kindle app on their computer, of course). It's only available through Amazon at the moment:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Ghost-Ocean-Whispering-Rooms-ebook/dp/B006KRI97I/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1323668895&sr=8-3

Apologies for the interruption to your scheduled fossils, knitting and random burblings about China. Normal service will be resumed shortly.

*No guarantees, mind. For those unaffected by the alleged boredom-relieving properties, I propose to advertise it as an over-the-counter soporific instead.

Sunday, 11 December 2011

And now for something completely different...

Saturday, 10 December 2011

Burgess Shale sponges

Dear all,

Apologies for the recent silence… we’ve been trying to finish off all sorts of things before the end of the year, and are flying back to the UK tomorrow for a “holiday”. This actually means going to a conference and a couple of museum visits as well, plus I’ve just been told I’ve got a couple of reports to write up and an hour-long presentation to do as soon as I get back, but we’re still looking forward to a decent break. You never know, we might even manage a blog post or two…

This one I wanted to write as a belated little something about the Burgess Shale. I spent three weeks working in Toronto, so perhaps you’re curious why..? Or perhaps not – but I’m telling you anyway. The reason is, the Burgess Shale contains some of the most astounding fossils to be found anywhere in the world. From the point of view of sponges, they probably are the best anywhere. The fossils come from a series of spectacular locations high in the Rockies in British Columbia. I’ve not been there yet, but I’ve now been invited to join in their fieldwork when I get a chance, which is a deeply exciting prospect.

These rocks are famous because they preserve soft-bodied animals and plants as well as the ones with skeletons – an entire menagerie of weird and wonderful creatures, from very early in the history of animals. They’re middle Cambrian in age (about 505 million years ago), and when discovered over a century ago, they gave us a first glimpse of what the squidgy things were doing at this point in history. The site was made famous by Stephen J. Gould’s book ‘Wonderful Life’, and has now entered mainstream culture through more books, magazines and television. For some reason, metre-long predators with pineapple-ring mouths and huge grasping appendages (Anomalocaris) and strange walking worms with enormous spines on their back (Hallucigenia) have managed to grab hold of popular attention. Strangely, though, the sponges are normally used as a background – literally. In reconstructions, all the interesting creatures are invariably seen scuttling in, on or around the sponges. It’s just not fair, and this is a little attempt to set things straight.

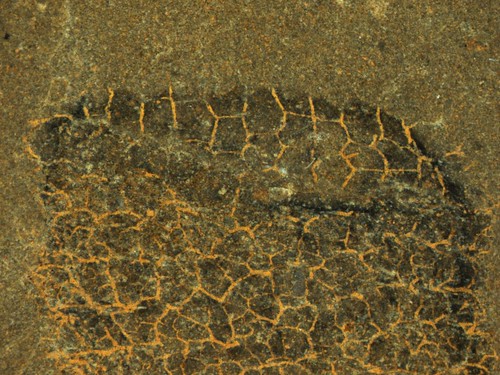

The sponges of the Burgess Shale have been studied in exhaustive detail three times – by Charles Doolittle Walcott (the site’s discoverer) in 1920, by J. Keith Rigby in 1986, and by Rigby and Des Collins in 2004. At each stage the diversity has increased, and it now stands at something near 50 species. Some of these are known from other sites around the world, in Utah or China, but many are endemic and have never been seen elsewhere. Several represent the only example of entire families of sponges in the fossil record, and most of the rest are the best examples. Take this picture here. It’s a sponge called Vauxia bellula, described originally by Walcott, so it’s very well known. This fossil is just astonishing. There are actually three levels of preservation here, and normally you don’t get any of them. The easiest to preserve is probably the organic meshwork that forms the orange lines; I’ve seen this type of preservation once from Scotland, and once from Herefordshire, and it’s also found in the Cambrian faunas of China and a few other famous fossil faunas. This is the type of material that your bath sponge is made of – in fact, it’s probably close to being a direct ancestor of that group. Bath sponges do not generally fossilise at all – they rot away and vanish before they can be preserved. In this case, it seems to have been preserved through being replaced by iron pyrite – fools’ gold – and then weathered to rust. And that’s the easiest bit, remember.

Under a microscope, the fibres are cored by truly tiny spicules. These were originally silica (opal-A), which dissolves very easily in warm water, but is more stable in the deep oceans. Despite the fact that they don’t rot away, these spicules are so tiny that they rapidly dissolve – you hardly ever see sponges with type of skeleton in the fossil record. Even in the famous fossil deposits of China you don’t see them, although I have reason to believe they were probably there. It also takes a different type of preservation to keep the spicules than it does to preserve the fibres they’re embedded in. So, to preserve the spicules as well as the fibres is really astounding.

But what about the third part? Well, you see that black stain covering the entire sponge? That, it appears, is the soft tissue of the sponge, the gooey jelly that has no chance of being fossilised at all. And best of all, that really does appear to be carbon – it’s a remnant of the original organic tissues, preserved without being turned into a mineral. This is the truly staggering bit about the Burgess Shale, and the real mystery behind the preservation of its fossils. To preserve really soft organic materials like this, you need to stop bacteria eating it – and there’s your problem. Take away all oxygen? No problem – the methanogens and sulphate reducers get to work instead. Highly acidic conditions? Not an issue for some of them. Boiling water and toxic metals? Sounds like a holiday for some groups of Archaea. For whatever conditions you can imagine in the sea where the Burgess Shale formed, there should have been absolutely no problem at all with bacteria living in the sediment. So how on earth did these fossils survive?

There are a long list of papers that have tried to address this, some with considerable success. Most of them, however, have focussed on other aspects of the preservation – the clay mineral films that coated the fossils, the calcium phosphate that formed in their digestive tracts, or the bits of pyrite that replaced certain structures. As far as I know, and despite some very intriguing suggestions, the organic carbon is still a mystery…

But what do I care? From my point of view, the result is that I get access to the most exquisite fossil sponges anywhere in the world, and can see both the skeletons and the soft tissues. And when you can all this, there are surprises – things that have been overlooked, despite those three monographic papers. There are vauxiids – sponges related to this one here – with a long, soft peduncle, and the soft tissue separated from the cage of the skeleton. There are others with utterly bizarre, unique spicules making up their skeleton, but with the strange bits composed of organic matter rather than opal. There are some… but no, I can’t tell you about that yet. That’s just too weird, and I don’t even know how to describe it. Let’s just say, for now, that there is more to these sponges than meets the eye. If we didn’t know better, we might think that they were much more complicated organisms way back in the Cambrian than they are now. Of course, we do know better… right?

For more information on this wonderful fauna and a whole stack of fabulous photos, please visit the recently launched website at: www.burgess-shale.rom.on.ca

Tuesday, 29 November 2011

Guanling Lagerstätte

One of the places I went to on my recent South China trip was the Guanling Lagerstätte. This is Late Triassic in age, about 220 million years old or so – so considerably younger than the rocks we normally look at. As is often the case in China, the fossil site has been made into a museum. There is a purpose-built building housing a lot of fossil material and a short walking trail around some of the outcrops. Some of the larger fossils (mostly ichthyosaurs) have been left in situ and had protective shelters built around them.

The photo shows slabs with lots of crinoids (sea lilies) on display in the museum. The crinoids are thought to have been attached to floating logs (although it’s only fair to say that this isn’t universally accepted, and the crinoids may have grown on sunken logs on the sea floor instead).

More photographs on flickr, showing marine reptiles, crinoids and their logs, and more of the museum displays.

Lucy

Saturday, 5 November 2011

Garden at Huanguoshu waterfall

It’s been a busy few weeks. After I came back from the conference in the US, I went off to Guizhou Province, South China for two weeks of fieldwork. The first week was with an Argentinian graptolite worker who was visiting Nanjing, so we went around already known sites. Some of them I had seen before, but it’s always good to go back to places, especially as I found a couple of sponges! For part of the week I “attended” the conference of the Palaeontological Society of China. “Attended” because I only went to the opening ceremony, and the rest of the time either worked in my hotel room or went to various interesting tourist sites with the Argentinian. There was little point in attending the talks, as they were entirely in Chinese and my language skills are not yet good enough to understand much.

The photo was taken in a garden at one of the sites we visited, called Huangguoshu Waterfall. I thought it looked like a stereotypically Chinese scene. The waterfall itself was about a hundred metres long, and there was a cave behind it, so it was possible to walk all the way round. Pictures of the waterfall are on my flickr photostream (click on the photo to follow the link).

The second week of fieldwork I went back to a site I had collected from earlier this year. I went to the site looking for graptolites, but also found various interesting things including worms. This time the worms were a bit lax in coming forward – none were found until the last hour of fieldwork, and then three came along in quick succession! I’m currently writing up a paper for publication, so more details will be forthcoming once that comes out.

Joe is currently in Canada looking at Burgess Shale sponges. I expect he will do a blog post about his adventures sometime.

Lucy

Saturday, 15 October 2011

Downtown Minneapolis

Perks of the Job

I’ve often heard it said that conferences are an excuse to have an expensive jolly, and justify it to the management. Too right. But that doesn’t mean it’s not important.

Last week we were in Minneapolis, Minnesota, for the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America. This is probably the biggest meeting we’ve been to, with something like 10,000 participants across all of the earth and planetary sciences. I reckon there were only a few hundred palaeontologists there, but that’s still a sizeable gathering (does anyone know the collective noun for palaeontologists? I dread to think…). For four days we mingled, muttered, harangued and bought drinks for each other, and we might even have learned something – all at the expense of a research grant (we used to pay for it ourselves, but now we live in luxury we can afford perhaps one of these per year). So how can we possibly justify jetting off to the other side of the world, staying in a hotel (well, hostel in our case) and eating in restaurants every night (well, most of them)?

Conferences are all about communication and collaboration. At a good conference, I am always amazed by what is achieved. Attending a conference in principle entails sitting down and listening to people present their work in 15-minute slots, from 8 in the morning until 5 at night, and slotting in the poster sessions between and after. In reality, there’s a lot more to it. There are times when the talks are really not relevant, and you go and talk to someone instead, but for much of the time you’re being presented with work that you otherwise wouldn’t read in paper form. In the process, you end up seeing all sorts of things that are relevant to you obliquely, or ideas that you can apply. For example, I saw a talk about the preservation of shell beds that showed that the most important aspect controlling what’s in them is not how much has been destroyed before burial, but rather how much mixing has gone on between the fossils from slightly different times. I don’t normally get to work on shell beds, but it’s an interesting idea regardless; it also matches what we see in modern bugs, where population proportions change dramatically from year to year. It’s one of many things we’re going to have to take into account in future.

If you’re going to a conference, you really ought to present. Firstly, a big part of the justification for going is that you are making your research accessible, and provides a stiff challenge to your results and reasoning: it’s an alternative to writing papers in a sense, although obviously it can never replace a permanent, published record of your ideas. Both of us gave talks this time, and they both went down surprisingly well – it must have been the quaint accents that did it. Lucy was talking about a comparison of three sites with soft-bodied fossils from the Early Ordovician (two of them new), and the announcement of new Lagerstätten always attracts attention. Her “exciting discoveries” were even mentioned in another talk on the last day, which is always nice – you know the message is getting through at that point. Mine was about early sponges, and how virtually everything that we think we know about them is probably wrong. It seems to have raised a few eyebrows, and one person made the “quotation mark” gesture when talking to me about hexactinellids, so again, the message obviously got through in some cases. This dispersal of ideas is crucial because hardly anyone works on sponges. Hopefully now some of the people who are seeing them in the field will have an idea of what might be important; aside from anything else, I had a few offers of collaborative projects across the world, and that can’t be bad.

Conference presentations also have the advantage that you can present ideas and discussions that are more speculative than the normal – things that might struggle with peer review, say. There was a wonderful example of that in Minneapolis, by Mark McMenamin (famed for his off-the-wall interpretations). In this case, he was interpreting a death assemblage of ten huge ichthyosaurs as being the result of predation by a Triassic Kraken. An apparently non-random arrangement of vertebrae in the remains he interpreted as being a deliberate, symbolic representation of its sucker array – the only non-human self-portrait in the fossil record. Now, I’m not saying that he’s right, but as he pointed out, cephalopods do have a high level of intelligence and are quite capable of catching things like sharks (e.g. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cA8zQw6gDNI). There’s also no doubt that ten big ichthyosaurs in one place, somewhere on the seabed off the coast, takes some explaining, and none of the previously suggested answers appear to work. Personally, I think it’s plausible… but that’s not really the point. This is what conferences can do – they present new ideas, new scenarios and new debates, and force us to think about them, no matter how daft they might first appear. Putting all those people in one place, for an intense few days of arguments and revelations, can’t help but lead to advances in the science.

So it’s not just a jolly. But yes, it is fabulous fun, and it means we get to see places we wouldn’t otherwise go. Lucy’s now back in China, and about to go on fieldwork in Guizhou, but I’ve stayed on in North America and am now in Toronto to work on the Burgess Shale sponges. More about that in a bit.

Sunday, 2 October 2011

Experiment in natural dyeing

I happen to find myself in need of a small amount of yellow wool, sufficient to crochet the beak and feet of a penguin (there is a good reason for this). I have white, black, red and green yarn, but no yellow. I could go out and buy a ball of yellow wool, but then I would be left with most of a ball of a colour that I don’t normally use. I could use red or green instead, but the resulting penguin would look a bit odd.

I decided to experiment with dyeing some of the white wool, using turmeric. I looked the subject up on the internet, and found that turmeric will work as a dye, but isn't very colourfast. This would be a problem if I wanted to make a garment, but isn't in this case, as the item I intend to make won't need to be washed very often.

I’ve done a little bit of dyeing before, and what is needed is not only some wool to dye and some colour to dye it with, but also something acid to make the colour stick. Vinegar or citric acid are often used. I don’t have any citric acid, and the only vinegar I have is very dark-coloured rice vinegar. I didn’t want to risk turning the wool black, so I bought a lemon and used the juice of one half.

On the left, the wool is soaking in a mixture of water and lemon juice. Making the wool wet before starting the dyeing process helps the colour to be taken up evenly. On the right is the prepared dye: I made it by mixing one teaspoonful of turmeric with a little hot water to the consistency of a thin paste. I then drained the soaking water and poured the turmeric mixture onto the wool. I used a plastic spoon to spread the paste, and squidged the yarn around with my fingers, to ensure even coverage.

I put the yarn into a plastic bag and steamed it in the rice cooker for about 15 minutes, then turned the rice cooker off and left everything to cool. I rinsed the yarn in the sink to remove any excess turmeric. Some of the colour came out at this point, but not much.

The experiment was a success: I now have yellow wool.

Friday, 23 September 2011

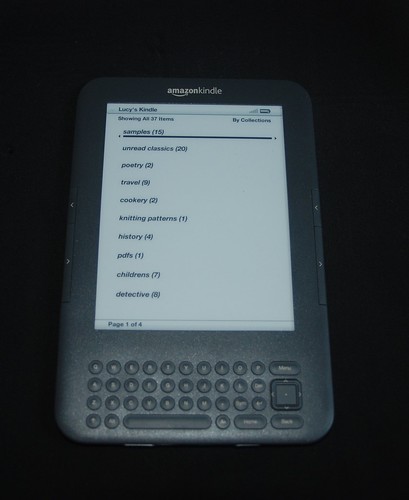

My kindle

When I was a child, the idea of a portable device that would hold thousands of books was science fiction. I recently bought one. Here it is.

There are several advantages to e-readers. The device is light in weight and small in size; smaller than an average paperback. The screen is easy to read, and the font size can be changed to allow for differing eyesight and lighting conditions. I can now carry enough books to be able to read through the entirety of a long flight – a thousand times over. I can read pdfs on the Kindle too, which means that I can now carry large chunks of my academic library with me. The device will even read some books out in a Stephen Hawking voice. The voice can be male (Stephen Hawking) or female (female version thereof) and the speed adjusted (very fast Stephen Hawking). Although the words are clear, the effect is slightly odd, as intonation is lacking. I don’t think I will be using this feature much, unless I buy A Brief History of Time, in which case it would be perfect.

Books are available almost instantly via the internet. This is certainly an advantage – no more waiting till I get to a bookshop/library before getting the next book in a series. This could also be a problem – I find I have to limit my visits to Amazon, although I usually manage to restrict myself to the free e-books.

There are some disadvantages to e-readers, too. I find they're not so good for things other than plain text. The screen only displays shades of grey, and some images just don't look right unless they're in colour. Also, flipping between an image and its caption is a nuisance, and even more so if you want to check something three pages back - for some things paper is definitely better! This isn’t a problem for most fiction, but for academic use it is often easier to print something out than to try to read it on-screen.

The most serious disadvantage of the Kindle is that it is an electronic device, which means that it has a finite (and not very long) life. Many of my paper books will be passed on to succeeding generations, but I am certain that my Kindle will not be. Even if it doesn’t suffer an accident that a paper book would have survived (for example, being dropped onto a hard surface), these things just die after a while. I can of course buy a new one and continue to read all the same books, as Amazon keeps a list of the ones I have downloaded. This will probably work out quite well, as I will have saved enough on not buying paper books (usually more expensive than the electronic version) to be able to afford another e-reader. However, it does mean that I have to keep spending money in order to keep reading items that I already own.

All in all, for my situation, in which books (at least ones that I can read) are expensive and the selection is limited, it's perfect. I will be using it mostly for fiction books, and not for academic texts. I certainly won’t be giving up buying paper books, but for light entertainment, where I am not too concerned about keeping a permanent copy, the Kindle will do nicely.

Lucy