Finally! It’s taken us long enough, but at last we’ve got one of our major new sites in Wales in print. It’s coming out in the journal Geology (quite a major one, so fairly exciting) next month, and is now available online:

http://geology.gsapubs.org/content/early/2011/08/05/G32143.1.abstract (if you don’t want to pay for it – and who would? - just send us a message and we’ll email you a copy).

The story behind this discovery is quite interesting. It’s been known as a major collecting site for decades, but in these beds the only things to be found are graptolites. So we thought as well, and we’d been going there for years, on and off. We then went along one day in 2004 with Talfan Barnie, at that time an undergrad volunteering with us for experience. Strangely, someone had dug a bit of a hole in the outcrop and left a pile of scree. We assumed it was because they were looking for trilobites (they wanted the quarry around the corner, in that case) and thought little of it. Talfan sat down by the hole and started pulling loose bits out of scree. After a few moments he handed us a big slab with a quizzical expression and said, “What’s this?”

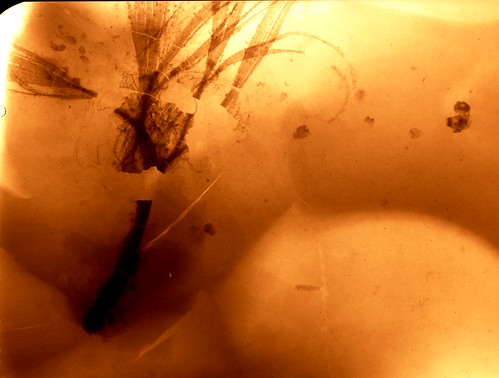

It was, needless to say, something amazing. It had a fibrous stalk, and a huge mass of filaments (tentacles, it turns out) coming out of one end. Scattered over the rest of the surface were bits of sponges, and strange pieces of things we can’t quite identify. The main fossil was similar to the one you see here (although this one doesn’t show the tentacles, and the stalk is wrapped back over itself). It’s a solitary hydrozoans – an extremely delicate creature rather like a very tall, slender sea anemone – and the chances of these being fossilised are extremely slim. The sponges you can see (little vase-shaped things) are also preserved as soft tissue – the spicules are there, but limited to the thick rim around the opening.

The fossils are preserved as iron pyrite (fools’ gold) in a soft black mudstone, which is pretty but difficult to work with. Luckily, though, it’s perfect for studying with X-rays, and that’s what you can see here. The pyrite blocks X-rays, similar to bone in a medical version, and we’ve inverted the image here to make it easier to see. Pyrite has some other problems, though – it’s very unstable. In the presence of water and oxygen, it rusts and turns into a horrible gunk with sulphuric acid and gypsum. The mudstone itself is also unworkable in the rain – it just turns to mud. In other words, in the traditional Welsh climate, the fossils don’t last long once they get close to the surface. It’s only by looking for really fresh material that you can find them at all, and it’s only by X-radiography that you can see and appreciate them. But boy, is it worth it.

We think there is a lot more to come from this fauna, although it will take time. The dominant fossils are the sponges and hydroids, but there are also worms, nautiloids with encrusters living on the shells, pieces of probable algae and as yet unidentified fragments, and exceedingly rare arthropods. The next job is to describe some of the more common species, but the best bits are surely still to come.

And no, we still have no idea who made that original hole – or whether they found anything.

Sunday, 21 August 2011

hidden fossils...

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment