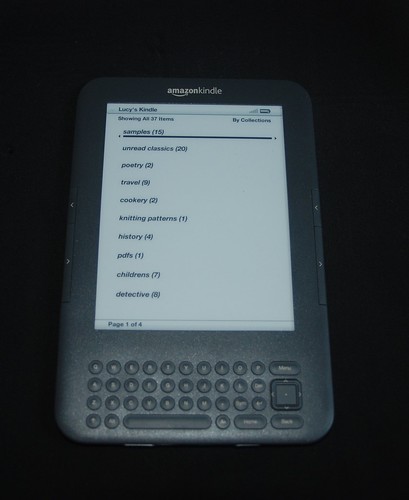

When I was a child, the idea of a portable device that would hold thousands of books was science fiction. I recently bought one. Here it is.

There are several advantages to e-readers. The device is light in weight and small in size; smaller than an average paperback. The screen is easy to read, and the font size can be changed to allow for differing eyesight and lighting conditions. I can now carry enough books to be able to read through the entirety of a long flight – a thousand times over. I can read pdfs on the Kindle too, which means that I can now carry large chunks of my academic library with me. The device will even read some books out in a Stephen Hawking voice. The voice can be male (Stephen Hawking) or female (female version thereof) and the speed adjusted (very fast Stephen Hawking). Although the words are clear, the effect is slightly odd, as intonation is lacking. I don’t think I will be using this feature much, unless I buy A Brief History of Time, in which case it would be perfect.

Books are available almost instantly via the internet. This is certainly an advantage – no more waiting till I get to a bookshop/library before getting the next book in a series. This could also be a problem – I find I have to limit my visits to Amazon, although I usually manage to restrict myself to the free e-books.

There are some disadvantages to e-readers, too. I find they're not so good for things other than plain text. The screen only displays shades of grey, and some images just don't look right unless they're in colour. Also, flipping between an image and its caption is a nuisance, and even more so if you want to check something three pages back - for some things paper is definitely better! This isn’t a problem for most fiction, but for academic use it is often easier to print something out than to try to read it on-screen.

The most serious disadvantage of the Kindle is that it is an electronic device, which means that it has a finite (and not very long) life. Many of my paper books will be passed on to succeeding generations, but I am certain that my Kindle will not be. Even if it doesn’t suffer an accident that a paper book would have survived (for example, being dropped onto a hard surface), these things just die after a while. I can of course buy a new one and continue to read all the same books, as Amazon keeps a list of the ones I have downloaded. This will probably work out quite well, as I will have saved enough on not buying paper books (usually more expensive than the electronic version) to be able to afford another e-reader. However, it does mean that I have to keep spending money in order to keep reading items that I already own.

All in all, for my situation, in which books (at least ones that I can read) are expensive and the selection is limited, it's perfect. I will be using it mostly for fiction books, and not for academic texts. I certainly won’t be giving up buying paper books, but for light entertainment, where I am not too concerned about keeping a permanent copy, the Kindle will do nicely.

Lucy

Friday, 23 September 2011

My kindle

Sunday, 18 September 2011

Caution - scientist at work!

This is what our office looks like. Joe is working, despite appearances - there is a good reason for having a cartoon character on his computer screen. I usually sit opposite him, with the printer between us. The room may look cluttered, but is in reality a very sophisticated filing system, in which the things we need most often – for example, tea mug – are most easily accessible. So, things like pens, printer and fruit bowl are on the desk between us, whereas dictionaries, envelopes and hammers are stored away in cupboards and drawers.

Our super-duper shiny new microscope is on a separate table, where there is plenty of room to draw. We normally keep it covered up unless we’re looking down it, to protect it from dust. The bit sticking out on the right of the microscope body is the camera lucida attachment. This is a wonderful device incorporating a mirror that allows the viewer to look at a fossil down the microscope and also see the paper to be drawn on. This allows one to make an accurate drawing just by going around the edges of the fossil – invaluable to those with little artistic ability.

The blue trays contain a small proportion of the fossils that we have to work with here. Most of the specimens are stored in the same type of tray on some large bookcases, but they don’t all fit there. This is another incentive to publish things quickly, before we run out of space altogether.

The windows are new; they were fitted in February, when the temperatures were below freezing. New ones were very necessary, as there was a pane of glass missing from the old ones, and they were very draughty in general. There was an insect screen concealing the missing pane, so it took us a while to work out where the icy blasts of air were coming from, and why the room never seemed to get warm.

There are more details of the things you can see, and other views of the office, on my flickr photostream (click on the photo to follow the link).

Lucy

Sunday, 11 September 2011

more little neighbours

It's been a while since we discussed some of our little multi-leggedy neighbours, so you deserve another installment.

At the end of our corridor, someone has placed some stacks of trays with rock samples outside their office. It's a nice quiet place with comfortable nooks and crannies... there are always open windows as well, so lots of small things for a hungry resident to entertain itself with. The resident in question is a uropygid, also known as a thelyphonid, a whip-scorpion, or a vinegaroon (a bit like a macaroon, but less coconutty).

Including the tail, it's nearly 10 cm long, but the body is a mere 4 cm or so. The tail is a long, hair-like structure that appears to be a sensory device – it certainly doesn’t have a sting, I’m glad to say. Lucy’s glad to hear that too, given that she almost stepped on it in the darkened corridor. (Or should that be, it almost stepped on her? Either way.) They can tell where they’re going by using those weird stringy legs at the front. They’ve evolved these in parallel with the antennae of insects, because uropygids are arachnids, and as such have no antennae. If you watch one of these moving, it will be tapping around in front of itself with those legs, searching for something yummy; its eyes are not that great, although it’s not actually blind, so it probably relies mostly on these to find its prey. This peculiar use of its front legs makes for another parallel with insects, as they only have six legs that they can walk with.

The things at the front are the equivalent of the palps of spiders – they’re not legs, but they evolved from them, once upon a time. They’re now used mostly to catch their unwary prey (mostly insects and millipedes, I’ve heard). The reason for the apparent overkill (although search for amblypygids if you think these ones are good) is that they don’t have a venomous bite, so the damage has to be done with the claws – or at least they have to be sure of holding things still for as long as it takes to nibble through them. Apparently they can’t do much damage to a human handler, although I imagine they’re a bit prickly. I was planning to try with the one in the corridor, just out of curiosity, but my finger thought better of it at the last second. Nothing should look quite so determined to go straight through whatever is in its path.

So why the vinegaroon moniker? Well, they do have a defence mechanism: they can squirt acid at something chasing them. It’s only a weak acid – vinegar plus something extra – but I imagine it might be offputting. Unless, that is, it’s chased by someone who’s quite familiar with fish and chip shops, in which case I guess it’s a self-condimenting treat. But it’s much more fun just to admire it when we get bored of writing papers or doing some statistical analysis. And of course we can leave the door of our office ajar so we can hear the occasional scream from the far end.

For those of a nervous disposition, there aren’t any of these in Europe. Except in pet shops.

Sunday, 4 September 2011

Chinese supermarkets

Chinese supermarkets

We visit our local supermarket, handily situated at the end of our road, most days. As we don’t have a fridge, shopping every day is essential in hot weather, as many things won’t keep until the next day. Most of the supermarket would be fairly familiar for anyone familiar with those in the UK. There are sections for cleaning products, toiletries, bottled water, alcohol, fruit and vegetables, and a meat counter. I was surprised to find a lot of dairy products on sale, as I had thought the Chinese didn’t care for them. Milk and yoghurt are extremely popular, but cheese and butter aren’t, judging by the space allocated to them.

There are some differences, though. The fish section also includes frogs and turtles, and the fish really are fresh – you can tell by the way they are still swimming. The tea department occupies a lot of space, and has a large display of very expensive types of tea packed in nice boxes ready to give as gifts. Coffee is relegated to a different section, and mostly comes in little sachets with powdered milk and sugar already added. All the coffee the supermarket sells is instant; ground coffee is sold in imported food shops and is horrendously expensive.

There are some goods sold in the UK that are not found here in China. For example, I have not seen tinned food since I came here. Ready meals are unknown – the nearest equivalent is little trays of chopped meat or vegetables ready to be dumped into the wok. The selection of spices is limited, and is mostly different sorts of chilli.

Handily for us, there is an aisle of imported food. This contains such delights as pasta (imported from Spain), cornflakes (from Malaysia) and Danish Butter Cookies (Malaysia, again). There is a very small selection from Britain. One might think this would be something that could not otherwise be found in China, such as shortbread, or tinned haggis, or laverbread, or chicken tikka masala. No, none of these. It’s tea. Camomile, peppermint, English Breakfast and Earl Grey. Yes, China, home of tea, home to more tea-drinkers than anywhere else, is importing the stuff from the UK. Since I don’t quite believe it myself, I took a photograph as evidence.

Sunday, 28 August 2011

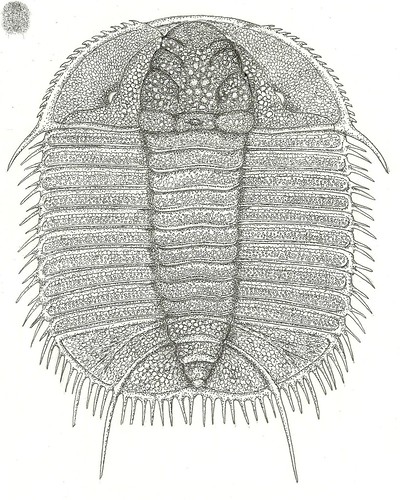

Meadowtownella serrata

Following the fossil theme, this is the reconstruction I did for another paper that's just come out (Conway & Botting, in Geological Magazine) . It's an odontopleurid trilobite from the Middle Ordovician of Llandrindod that Tim worked on for his MSci project, and a spectacularly spiky beastie it is too.

Why all those spines? Don't really know. The odontopleurids as a whole are characterised by very spiny outlines, but this one has more than most. What the function was, we're not clear on - it may be as simple as camouflage - it breaks up the outline on the sea floor, especially with all those tubercles on the surface. It may have made them less easy to eat, but you'd think that would only affect things that swallowed them whole. One curious fact that Tim uncovered is that in the genus Meadowtownella, the number of spines around the tail decreases with time (this one is the oldest yet described). However, it also occupied muddy areas rather than reef areas, which is bound to have had an effect. Jury's out on that one.

Another curiosity: this has never been found, even the tiniest fragment of it, anywhere except for one site. At that site, it's abundant - Tim collected hundreds of fragments - through about 60 m of mudstone. That's a long time - in the history of a volcanic island, it's a very long time. What was it about that small area that allowed it to thrive, when elsewhere it didn't seem to exist at all? Is it just that it lived for a very short time, and this was the only place in the area where exactly the right age was exposed? Or was it to do with the oxygenation levels at the sea floor, or the need for a particular food source, which lived in that area..?

I'm getting an interesting perspective from all the time spent looking at modern bugs. The Cornish Shieldbug, for example, is restricted in the UK to one cove; there are historical records for another site in South Wales, but not for a very long time. The bug lives on sand dunes, and is associated with a common host plant (Galium verum). It can also fly. Why hasn't it got anywhere else? It's thriving at its home, but doesn't seem able to expand. There is presumably something specific in the habitat that we're not quite understanding, and it's not by any means the only example of this, even among UK bugs.

How much harder is it to work out for the fossil record? We don't even know the habitat preferences of many species, and for some entire groups, such as planktonic graptolites, we don't even have anything modern to compare them with. We do know that some trilobites were quite widespread - Ogyginus corndensis, for example, turns up in a wide variety of environments. Others, like Meadowtownella were much more restricted. Many species were simply very, very rare - only one specimen of several species of trilobites have ever been found in the Builth Inlier - so what we know about those can be written on the back of an odontopleurid.

This to me is where palaeontology gets really interesting... it's not just finding the things that matters, but really understanding them. Interpreting the ancient past when you only have a few scraps of information to go on is a challenge, certainly, but it's also a wonderful journey of discovery...

reference: http://www.rairo-ita.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8351175

Celtic cross stitch

Via Flickr:

My favourite part of any cross stitch project is the outlining. After all the long work of doing the cross stitches, the back stitch goes quickly, and really makes the piece look finished. Here, the black lines turn random bits of yellow into a Celtic design, and the separation of colours into blocks makes the blue and green show up more clearly.

This is a small kit for a coaster that my mother gave me. I had to modify it slightly from the design given. Firstly, the design was yellow, green and red, not yellow, green and blue as I have done it. This is because, instead of having two lots of red thread, the kit contained one lot of red and one of blue. I decided I liked the blue better, so used that, and was very frugal with the amounts given. There would have been enough thread, except that I managed to lose the last of the blue. The original design had the little twirly bits around the edge filled in, so I unpicked those and thereby gained enough thread to finish off the centre.

Now all I have to do is finish the outlining, carefully wash the embroidery, trim it to size and put it in the coaster.

In other news, we've had three papers published this week. Joe has already blogged about one of them. It's gratifying to report that quite a number of people seem to find it interesting.

Lucy

Sunday, 21 August 2011

hidden fossils...

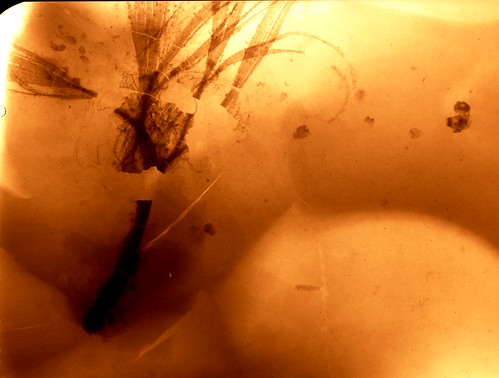

Finally! It’s taken us long enough, but at last we’ve got one of our major new sites in Wales in print. It’s coming out in the journal Geology (quite a major one, so fairly exciting) next month, and is now available online:

http://geology.gsapubs.org/content/early/2011/08/05/G32143.1.abstract (if you don’t want to pay for it – and who would? - just send us a message and we’ll email you a copy).

The story behind this discovery is quite interesting. It’s been known as a major collecting site for decades, but in these beds the only things to be found are graptolites. So we thought as well, and we’d been going there for years, on and off. We then went along one day in 2004 with Talfan Barnie, at that time an undergrad volunteering with us for experience. Strangely, someone had dug a bit of a hole in the outcrop and left a pile of scree. We assumed it was because they were looking for trilobites (they wanted the quarry around the corner, in that case) and thought little of it. Talfan sat down by the hole and started pulling loose bits out of scree. After a few moments he handed us a big slab with a quizzical expression and said, “What’s this?”

It was, needless to say, something amazing. It had a fibrous stalk, and a huge mass of filaments (tentacles, it turns out) coming out of one end. Scattered over the rest of the surface were bits of sponges, and strange pieces of things we can’t quite identify. The main fossil was similar to the one you see here (although this one doesn’t show the tentacles, and the stalk is wrapped back over itself). It’s a solitary hydrozoans – an extremely delicate creature rather like a very tall, slender sea anemone – and the chances of these being fossilised are extremely slim. The sponges you can see (little vase-shaped things) are also preserved as soft tissue – the spicules are there, but limited to the thick rim around the opening.

The fossils are preserved as iron pyrite (fools’ gold) in a soft black mudstone, which is pretty but difficult to work with. Luckily, though, it’s perfect for studying with X-rays, and that’s what you can see here. The pyrite blocks X-rays, similar to bone in a medical version, and we’ve inverted the image here to make it easier to see. Pyrite has some other problems, though – it’s very unstable. In the presence of water and oxygen, it rusts and turns into a horrible gunk with sulphuric acid and gypsum. The mudstone itself is also unworkable in the rain – it just turns to mud. In other words, in the traditional Welsh climate, the fossils don’t last long once they get close to the surface. It’s only by looking for really fresh material that you can find them at all, and it’s only by X-radiography that you can see and appreciate them. But boy, is it worth it.

We think there is a lot more to come from this fauna, although it will take time. The dominant fossils are the sponges and hydroids, but there are also worms, nautiloids with encrusters living on the shells, pieces of probable algae and as yet unidentified fragments, and exceedingly rare arthropods. The next job is to describe some of the more common species, but the best bits are surely still to come.

And no, we still have no idea who made that original hole – or whether they found anything.